Injuries suffered more than 70 years ago to Pvt. Grandon Tolstedt ’48 reshaped his right hand, left leg and his career.

Tolstedt was a 20-year-old first scout with the 104th Infantry Division when fragments from a German mortar shell left him with compound fractures—4 inches of bone was shot out of his lower left leg and his right elbow joint was shattered, healing solid with no joint movement and the ulnar nerve was cut so two fingers don’t function.

That was Nov. 20, 1944. It was late August 1946 before his hospital stays ended. His nearly two years in hospitals gave him direction for the next 46 years of his career as a general surgeon.

Tolstedt came to State in 1941 from a farm west of Herreid in north-central South Dakota, starting as an ag major.

That lasted two quarters. “I realized I wanted to do something different than agriculture†and switched to chemistry, said Tolstedt, now 91 and a resident of Rockford, Illinois.

But his life was changing well before he changed majors. Japan attacked Pearl Harbor Dec. 7, 1941. After the U.S. declared war against the Axis powers, nothing was ever the same for State students of that era.

Tolstedt’s freshman class had 494 students; by the next year it was down to 273.

Active duty began in ’43

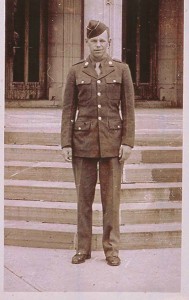

Grandon Tolstedt poses in Colorado before Company A of the 104th Division shipped to Europe in August 1944.

Most young men either volunteered or were drafted. Tolstedt joined the U.S. Army Reserves in November 1942. He stayed in college until called to active duty in April 1943. “They encouraged us to join the Army with the agreement we could stay in school for a number of months. … It was a difficult time because we knew what was going to happen to us. Studying was difficult,†he said.

Like all freshman and sophomore males of his era, Tolstedt was in ROTC.

When he went into active duty, Tolstedt was slotted for the dangerous work of an infantryman. After training at Camp Wolters, Texas; Rutgers University in New Jersey and Camp Carson, Colorado; Company A of the 104th Division headed for Europe in August 1944 and entered battle in Holland in mid-October.

Marching into battle

The division was then transferred to the First Army to battle in the northern part of the Hurtgen Forest west of the Belgian-Germany border.

As first scout, Tolstedt was part of an advance unit that served to engage the enemy and keep German troops anchored in their position while other Allies sought to outflank the front line. Tolstedt describes his duties in “Private Tolstedt and Friends,†one of 20 books he has self-published on a variety of topics.

He doesn’t give details on the Nov. 20, 1944, attack, but in a phone interview said a mortar shell fell two or three feet from him.

Tolstedt was among 15 to 20 Americans injured in the attack. He’s thankful he wasn’t among the four or five killed. “I was injured at 5 p.m. It took until 11 p.m. to get me back to the aid station. By that time, my blood pressure was very low,†he said. However, he never thought he would die.

“I knew they were going to get me out of there pretty soon. It took four guys with a stretcher to get me out†of the gully where he was entrenched.

Not safe in a hospital

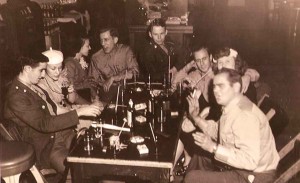

While Tolstedt spent three months at Baxter Hospital, there was time to be social. He is next to a woman on the table’s right side.

After receiving treatment at field aid stations, Tolstedt was evacuated to a hospital in Eupem, Belgium. A week later he was transferred via Army ambulance to a hospital at Liege, Belgium, west of the front lines.

Tolstedt wrote that he was happy to be farther away from the sounds of battle, but “was a mess. There was a cast on his chest and right arm. Another cast was on his left leg. Blood seeped through the plaster casts. There were bandages on his right leg and left arm. Private Tolstedt had not shaved for over a week and had not had a haircut for over two months.

In a phone interview, he said about his hospitalization, “It was not easy. I had heavy casts on. I felt I would survive, but there was a fair amount of pain.â€

From one hospital to another

Tolstedt poses at Baxter Hospital, Spokane, Washington, where he spent three months in 1945 recovering from a Nov. 20, 1944, mortar shell attack.

But smiles came easily when word spread that all the patients would leave by train for an American hospital in Paris, where he stayed for five days, and in December arrived at a hospital in Bristol, England, where he stayed until March 1945. Then he sailed on the Queen Mary to a hospital in Glasgow, Scotland.

While at Glasgow, he received his Purple Heart in a somber ceremony. “It was a nice medal, but failed to have any therapeutic value,†he wrote.

The Queen Mary then took him to New York, where Tolstedt got on a train for a hospital in Spokane, Washington.

After three months there, he traveled by train to a Galesburg, Illinois, hospital. “That’s where I had a lot of treatment,†he said. There were multiple operations, including skin, nerve and bone grafts. Finally, in late August 1946 he was discharged from the hospital and the Army.

Another vet back on campus

That fall Tolstedt arrived at State College on crutches and with a 90 percent disability rating.

That kept him from playing in the band (he played clarinet under Carl ‘Christy’ Christensen his first two years at State), but it didn’t keep him from driving and studying hard. His roommate in East Men’s Hall was Howard Hanson, who Tolstedt said was the first blind student to

attend State.

During his later hospitalizations, Tolstedt read anything he could get his hands on. “It improved my academic ability immensely,†he said.

The 21 months he spent in hospitals also caused him to think about a medical career. “By the time I got out of the hospital, I didn’t know anything else. I had actually learned some things and I thought it was a fascinating occupation,†said Tolstedt, who added that he was encouraged by an uncle who was a physician.

On to medical training

At the time of the famous canceled 1942 Hobo Day, this group of bearded students hailed from Campbell County. On the far left is Tolstedt, a sophomore from Herreid. Next is Mike Schaefbauer, a freshman from Herreid who joined the U.S. Navy and saw combat on the Bunker Hill aircraft carrier. Next to them, are, respectively, Elmer Reierson and Louis Dornbush, both from Pollock. All survived. Tolstedt and Dornbush completed their degrees at State: Tolstedt in 1948 and Dornbush in 1949.

Following his graduation from State in 1948 with a chemistry degree, he did a year of postgraduate study in chemistry at the University of Wisconsin.

Tolstedt entered Northwestern Medical School in Chicago in 1949, graduated in 1953, spent the next 10 years at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in Seattle with an internship and specialty training and then the last four years as staff surgeon. He was in private practice in Bismarck, North Dakota, from 1963 to 1984.

His disabilities required a number of adaptions, but “it’s surprising how much one could do if you try,†Tolstedt said.

The natural right-hander became ambidextrous. “I learned very quickly how to eat with my left hand,†he quipped. Gradually, he regained some use of his right hand. “My fourth and fifth fingers were paralyzed. The other three could be used quite well for most activities,†Tolstedt said.

“In surgery, knot tying was essential. I had to learn to tie with my left hand,†Tolstedt said. He used his right hand for scissors.

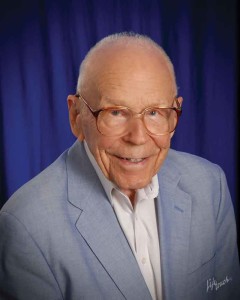

Retirement years remain active

When he retired from practice in Bismarck, Tolstedt returned to Seattle, but flew back weekly to teach surgical residents at the United States Public Health Indian Hospital in Belcourt, N.D., and work at Indian Health Service surgical clinics in Sisseton and Eagle Butte, S.D., and Fort Yates and Fort Berthold, N.D.

He fully retired in 1992, a year before his wife, Ardis Candy, whom he met at the University of Wisconsin, died.

In 1995, he married Phyllis Hansen, whose first husband was Tolstedt’s former college roommate Howard. She died in September 2003. In 2005, he married his current wife, Kay Hotchkiss, whom he has known since 1948 and whose first husband served in the Army with Tolstedt.

They live at a retirement community in Rockford, where he writes daily for an hour and goes to the fitness center twice a day.

As he thinks about a career born out of a mortar shell attack, Tolstedt doesn’t go so far as to call it a blessing in disguise. But life as a surgeon “was a very satisfying career. I enjoyed getting people well if I possibly could.â€

Dave Graves

Really a great article! My dad was Elmer Reierson who was a life long friend of Grandon Toldstedt.

Thanks for your work on this story.

Julie Brandner