“You can’t go back and change the beginning, but you can start where you are and change the ending.”

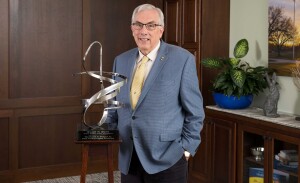

South Dakota State University President Barry Dunn quoted C.S. Lewis while accepting his Harold W. McGraw Jr. Prize in Higher Education on Nov. 3.

Announced as a McGraw winner in September, Dunn was recognized with the prestigious award for his work with the Wokini Initiative, improving college access for Native Americans, advancing the principles of equity and inclusion, and demonstrating the power of education to elevate human potential.

The Wokini Initiative was launched in 2016 during Dunn’s inaugural address. The McGraw award recognizes the work of many at SDSU on the initiative’s behalf.

“We committed ourselves to ambitious goals to enable the members of the nine tribal nations in our state to succeed at South Dakota State. We’ve adopted a holistic approach to student success, addressing financial, social, cultural, mental health and educational needs on an individual basis,” Dunn said.

Because of generous donors, SDSU built the American Indian Student Center in the heart of campus and has nearly $19 million in an endowed scholarship fund. Native American enrollments have increased, along with retention and graduation rates.

With the authorization of federal legislation—New Beginnings for Tribal Students—and with annual appropriations for funding, land-grant universities and tribal colleges and universities across the country now have tens of millions of dollars of new money to assist tribal students.

But Dunn recognizes there’s still a lot of work to do.

“Following the tumultuous period of western expansion into the homelands of the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota people in the 1850s through the 1880s, Sitting Bull, chief of the Hunkpapa Tribe of the Lakota people, provided the following challenge: ’Let us put our minds together and see what life we can make for our children.’

“Quite frankly, and sadly, 140 years later, we have fallen short in meeting his challenge and are still seeking ways to build a sustainable future for his heirs,” Dunn told the crowd at the McGraw banquet in New York City.

South Dakota State University has accomplished many things and has much to be proud of in its 141-year history, Dunn said.

“But it, too, has struggled to meet not only Sitting Bull’s challenge, but also to fulfill our land-grant mission of providing access to the benefits of higher education for all the citizens of South Dakota, of which nearly 10% are Lakota, Dakota or Nakota. Historically, enrollments of these students in South Dakota State have been very low, and their graduation rate has been unacceptable,” Dunn said.

“When I became president of South Dakota State, I challenged our university to use our collective imaginations to meet the challenges of the future and at the same time to re-imagine how we address lingering challenges.”

Dunn said in order to change the ending for the indigenous people of the state, the university basically started from scratch, “owning our past, acknowledging our responsibility, and dedicating the annual flow of funds from our land-grant land to benefit the heirs from whom the land was taken so very long ago.”

Dunn said he was honored and humbled and thanked a list of people who have supported him through the years: his wife, Jane ’77; brothers Gregg and Roger; and his friend, Marshall Matz.

“And a special thank you to my leadership team at South Dakota State University, who have never wavered in their support of the Wokini Initiative and who have worked tirelessly to bring it to life,” Dunn said.

“In our seventh year, and recognizing that we have a long way to go, we have had early success in building lasting change into our university to better serve Native American students.”

Dunn also recognized his parents.

“They passed long ago, but I am so grateful for their unconditional love and support, plus instilling in me a set of core values that have been the foundation of my life.

“My mother, Sarah, was born in the humblest of conditions on the Rosebud Indian Reservation. Because she was Lakota, she was not considered a citizen of the United States. Her father, my grandfather, received his early education in a boarding school.

“When Sarah graduated from college, less than 4% of the women in America had a college degree. Unfortunately, I don’t know all the details of how this little girl from Rosebud found her way and accomplished so much, but I gratefully stand on her shoulders and dedicate this award to her memory.”

Dunn is among three 2022 winners of the Harold W. McGraw Jr. Prize in Education, announced by the McGraw Family Foundation and the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education. He and fellow recipients Cheryl Logan, superintendent of Omaha Public Schools and winner of the Pre-K–12 Education Prize, and Roy Pea of Stanford University, winner of the Learning Science Research Prize, each received $50,000 and an awards sculpture.

“The McGraw Prize was established in 1988 to honor my father’s commitment to literacy and education and to shine a spotlight on innovative and dedicated educators who empower our students and enhance our society,” said Harold McGraw III, former chairman, CEO and president of The McGraw-Hill Companies. “I salute this year’s winners—Cheryl Logan, Barry Dunn and Roy Pea—who meet the highest standards of excellence and who have changed the lives of so many by their leadership and passion.”

Jill Fier