Three survivors continue legacy of WWII servicemen

Tom Brokaw called them “The Greatest Generation.â€

The servicemen who formed our U.S. Army, Navy and Army Air Corps during World War II created legacies that continue to be revered three-quarters of a century later. At South Dakota State, no legacy is better known than the ’44 Kings, a group of servicemen who would have graduated in 1944 had Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor not brought the nation into WWII.

Today, more than 75 years after the group of 52 young men began their on-campus journey with Uncle Sam, three veterans have defied the odds of mortality.

Ron Peterson, 96, of Brookings, Don Thompson, 98, of Cary, North Carolina, and Harold Lohr, 96, of Berlin, Massachusetts, are still alive. Most all of the 52 were counted as survivors when the group held a 1985 reunion. (There were only two wartime casualties.) A letter in advance of that reunion gave the ’44 Kings another notch in their legend.

A letter from Bryan Baughman to fellow King Thomas Lyons gave birth to the now-famed last man’s club.

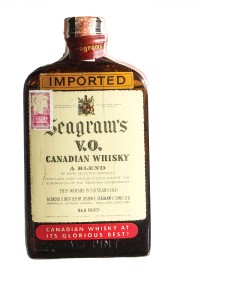

Baughman wrote, “Someone suggested that we form a last man’s club. I have a bottle of Seagram’s VO (dated 1937) that I found in the trunk of the old Buick after the Barn Dance in March 1943 which I will donate.†Marion Davies DeKraay, the honorary cadet colonel for the Kings, was the keeper of the bottle until her death in 2001. The award is housed in the Alumni Association.

None of the three survivors is anxious to break the bottle’s seal.

“It’s a relic and nobody should be able to open it up. It’s a memento of something important,†said Lohr. Thompson and Peterson agreed that the legacy of the bottle should be maintained. Thompson wondered if it might represent an opportunity for Seagram’s to create a scholarship for South Dakota State U.S. Army ROTC students.

Two years from graduation

Before the ’44 Kings became the ’44 Kings, they were just another bunch of young men trying to get a jump on their peers by getting a college education as the nation and state regained its feet from the double whammy of the great stock market crash of 1929 and the Dust Bowl years of the 1930s. State College had an enrollment of 1,358 in 1941-42.

By 1942-43, the enrollment was 1,195 with many of the males enlisting in the military or returning to the farm to cover for siblings who enlisted.

All males were required to take ROTC for their first

two years of college. The group who would become the ’44 Kings signed up for Advanced ROTC to be commissioned second lieutenants when they graduated two years later, supposedly 1944.

The late Sherwood Berg, who would become president of his alma mater in 1975, said in an earlier interview, “The plan presented to us was: Enroll in ROTC, which simultaneously enlisted you in the Reserve Corps, and you will graduate; and, you will be commissioned upon graduation.â€

A change in plans

The plan began with summer classes in 1942 and progressed as designed until March 18, 1943, when orders came out of the Office of the Commanding General in Omaha, Nebraska. The 52 privates in the State College infantry unit were “ordered to active duty†at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, by April 12, 1943.

There they would be processed and assigned to basic training in lieu of their second year of advanced ROTC training.

At 10 p.m. April 10, the community and college had a farewell program for the group at the Brookings Armory. The State College cheer squad and the women’s band, under the direction of Professor Carl “Christy†Christensen, joined in the event sponsored by the Students’ Association and civic organizations. The American Legion Post presented a gift box to each man. (Note: Other enlisted groups received similar send-offs.)

At Fort Snelling, the enlisted reserve students were screened, issued equipment, divided into two companies, got an introduction to kitchen patrol and other aspects of Army life, and then headed to Camp Wolters, Texas, for basic training.

After 17 weeks in training, the Army wasn’t ready to send out the unit, so it returned home, indirectly.

Back to Brookings

The men initially spent about a week in the basement of a dormitory at Grinnell College in Iowa because there was no housing for them at State. The soldiers arrived in Brookings Sept. 20-21, 1943, and settled into bunk beds in the basement of Wecota Hall, which had been the girls’ dorm.

“When we got back, we were very important people on campus,†the late B.J. Gottsleben said in an interview for the 2003 book “College on the Hill.â€

This bottle of whisky will go to the final survivor of the ’44 Kings. It is currently kept at the SDSU Alumni Association.

The late Bob Hedman said, “We were treated like kings on campus. We were upperclassmen; most of us were seniors. The local people knew us. A lot of the guys had girlfriends there.â€

Lohr recalled, “I am quite sure that the name ’44 Kings was given us by Vivian Volstorff (dean of women) at least partly because some of us complained about the restrictions imposed on the girls,

such as 10 o’clock curfews. I know that she attended our 1985 reunion as an honored guest.â€

While overall enrollment was down at State, an Army Specialized Training Program for well-qualified young men age 17 and older had been started by the military at State. Several hundred of the participants were housed on campus, Hedman recalled.

These students voluntarily joined the program and attended State on military scholarships. They were housed at Scobey Hall and had a full-day of all-soldier classes with regular college professors as their instructors.

A two-month campus reign

The Jack Rabbit yearbook reports that the last of 1,200 of these students left State June 1, 1946, as the program ended. In addition to these young trainees, there were 250 reserve officers and a small group of Army Engineering soldiers on camp.

Hedman says the term “kings†may have been given the group because of its superiority over the new specialized program enrollees.

The late Milton Sunde concurred. “When we got back to the campus, we had been ‘worked on’ pretty hard and thought we were tough. There were other armed forces on the campus. When we were marching on campus, we made the other marching units get off the sidewalk. This sort of got the ’44 Kings story going,†Sunde recalled.

The men expected to remain big men on campus until their spring 1944 graduation, when they would go to Officer Candidate School. But new orders arrived, and they boarded the train for Officer Candidate School in Fort Benning, Georgia, the day after Thanksgiving, 1943.

Graduation from Officer Candidate School was April 18, 1944. At this point, the men entered different infantry divisions and helped the Allies achieve V-E Day May 8, 1945.

After the war, many of the Kings made their way back to college in Brookings and many married. Some lived off-campus. Others lived in the married-student housing barracks. Many of the single guys were quartered in a wing of Scobey Hall. Again, they were the big men on campus.

Most graduated in 1947. The ’44 Kings returned to campus periodically for Hobo Day reunions and, of course, that 1985 gathering that made longevity another part of their legacy.

– Dave Graves