“Where there is no hope, the people perish.â€

This paraphrase of Scripture has been around long before 1925, but Hope certainly kept millions from perishing.

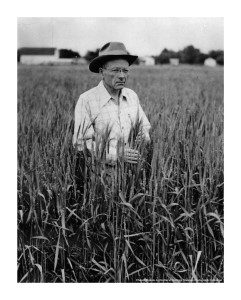

Hope is the name given to a variety of wheat introduced in 1925 by SDSU graduate Edgar McFadden at a time when wheat harvests were being decimated by black stem rust, a fungus that corrodes the stalk and shrivels production of wheat.

Wheat stem rust wasn’t new back then. It had been around for centuries. In fact, the Romans considered rust a spirit to be feared.

In McFadden’s time, starvation was to be feared. Rust tended to go in cycles, often in connection with weather patterns. During epidemic periods, it is estimated that 50 percent of a continent’s wheat production might be lost. Such severe reductions in yield could be the crushing blow to populations with already thin food supplies.

McFadden’s Hope wheat variety resisted the disease that was wiping out common varieties of his day.

As a result, people that would have otherwise starved had abundant access to bread because of genetics in Hope wheat. A 1947 Minneapolis Tribune article on McFadden put that number at 25 million people. Thanks to huge grain surpluses in the States during World War II, America could feed populations abroad.

Slept with seed as an infant

McFadden’s discovery didn’t come by accident. It was his dogged pursuit after what he witnessed at his family farm.

McFadden was born in 1891 in a small house seven miles northwest of Webster to parents of Irish heritage. His parents, James and Beatrice, had been teachers in New York state when they decided to try life as farmers. The McFadden home also served as a granary, a 1999 article in SDSU’s Farm and Home Research states.

“The baby’s bed was a grain bin filled with the next year’s seed wheat,†according to the article.

Talk about destiny.

Fungus foils family’s farming

But it wasn’t a future stirred with a silver spoon. In 1903, when McFadden was 12, his father was gored by a bull and nearly died. Edgar took over operations — planting the crops and watching the wheat mature to what looked to be a 40-bushel-per-acre crop. But just days before harvest, stalks broke and kernels shriveled.

The result was a five-bushel-per-acre harvest and a personal introduction to stem rust.

Welcome to Texas

A succession of bad crops was enough for the family to give up on farming and try ranching — in West Texas.

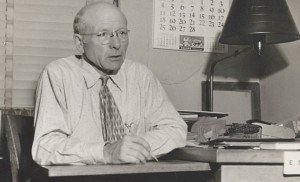

With the purchase of 600 acres south of Pecos, near the Rio Grande, the McFaddens set out to be cattle ranchers. Kevin Kephart, vice president for research at SDSU, has a photo of McFadden as a young man with shotgun, six-shooter, chaps and a cowboy hat.

And it wasn’t for show. It was life in West Texas in the years after the turn of the century and when Mexican fugitive/military leader Pancho Villa made excursions across the border.

While living there (1908-11), McFadden took pictures of Pancho Villa and his men. But he didn’t forget the wheat fields back home.

Follows wheat as custom harvester

In fact, each year McFadden would follow the wheat harvest north from Texas to the Dakotas. He worked on a custom harvest crew, “but he also was an intent observer,†says Kephart, an agronomist by background who is using his interest in history to do research on McFadden.

“He speculated that weather patterns would blow the rust from south to north, and that is indeed what was happening,†Kephart says.

It was the uncertainty of life in West Texas during the Pancho Villa era that pushed the McFaddens back north.

“I returned to South Dakota just in time to witness the big drought of June 1911 followed by an epidemic of stem rust which practically wiped out everything that the drought had not taken,†McFadden is quoted in the 1999 Farm and Home Research article.

“It is little wonder that I acquired a lasting impression of the vital importance of controlling drought and plant diseases.â€

Emmer provides an glimmer of hope

While there was little to harvest, McFadden did reap an observation that yielded Hope. A nearby patch of Yaroslav emmer, an ancient wheat, was robust and healthy. The feed grain had resisted rust that wiped out traditional spring wheat.

So McFadden entered South Dakota School of Agriculture in fall 1911 with an idea — what if emmer could be crossed with bread wheat?

Wheat breeders of that era considered it impossible. The plants flower at different times and their pollen is incompatible — emmer cells contain 28 chromosomes compared to bread wheat’s 42. However, his professor, Manley Champlin, encouraged him to try.

Perseverance leads to profound discovery

This 20-year-old who entered Aggie School with an eighth-grade education proved science wrong.

This 20-year-old who entered Aggie School with an eighth-grade education proved science wrong.

But it happened because all five-foot two-inches of McFadden’s frame was packed with perseverance and his work was overshadowed by providence.

“He took at least two years of preparation for this (crossing experiment) under Champlin,†Kephart explains. “He obtained seed from a single, rust-free plant of emmer from his farm and had a pure line strain of Marquis. He also tried crossing emmer with several other bread wheat varieties.â€

From a garden in Brookings

At the time, McFadden was living at a boarding house on the southwest corner of Eighth Avenue and Ninth Street.

He coaxed the landlady into giving up a corner of her garden. There he planted rows of emmer and other varieties. Bread wheats normally enter anthesis earlier than emmer. But in 1916, there were a few days when pollen shed overlapped, Farm and Home reported.

McFadden removed the emmer anthers and brushed the pollen from Marquis onto the emmer stigma, the journal states.

Scientists have since pinpointed the amount of time in hot July weather that wheat pollen stays viable. After the anther opens, it is less than five minutes, according to the Farm and Home Research article.

Harvest that fall yielded only a few shriveled seeds, but when spring 1917 arrived, McFadden dutifully planted them.

From one to 100

Only one seed grew, but McFadden nurtured it and in the fall he harvested 100 seeds. “He had to have made hundreds of crosses and he got one, single viable seed,†Kephart marvels. “None of those (100) seeds looked like they had any promise, but he then began his plant selection process.â€

The 100 seeds were planted in four, 12-foot-long rows in spring 1918 on the family’s Webster farm and McFadden soon graduated with a bachelor’s in agriculture.

Now it is McFadden who is selected. With America still involved in World War I, the 27-year-old gets notice from Uncle Sam to report to the Army. McFadden, who also was married May 4, 1918, leaves behind his passions — Mabelle Blakeslee and experimental wheat — for duty at Fort Lewis, Wash.

It is the wheat that brings him back.

He persuaded his commanding officer to grant him a harvest furlough in October. McFadden didn’t mention that his field was smaller than a garden plot.

Doing the unthinkable

Noel Vietmeyer tells part of the McFadden story in his 2004 book “Our Daily Bread†on wheat breeder and Nobel Laureate Norman Borlaug.

Looking at his 1918 crop, “McFadden found that his specimens had segregated into two basic forms — some resembled emmer and were practically stem-rust free; the rest resembled Marquis and were practically dead.

He had gotten nowhere.

“However, by checking plant by plant he located two Marquis lookalikes that remained rust free. Against all odds, the 27-year-old dabbler had done the unthinkable and got emmer genes to merge into bread-wheat chromosomes …

“Lovingly storing their 200 seeds in two carefully labeled coffee cans, he dutifully returned to boot camp for more training to fight, perhaps to die, in France,†Vietmeyer writes.

Continuing, he writes, “However, within a month it was World War I that died. McFadden shuffled back to South Dakota to join the U.S. Department of Agriculture (at the Highmore experiment station). On the side, though, he kept building his brainchild.

“The offspring should have been as sterile as mules; instead, they flowered and fertilized themselves.â€

Setbacks mount, but Hope inspires

The seeds bore potential, but the variety certainly was not perfected. Before it could be, McFadden lost his job in 1921 because Congress cut funding to USDA. He went back home to farm and spend hours in his

back-porch lab.

McFadden’s string of ill fortune was just beginning. Drought shriveled his harvest in 1921. Hail pummeled his yield in 1922. In 1923, Day County had the biggest outbreak of stem rust that it had ever seen. McFadden, who by this time also had a daughter, was on a financial tightrope.

But he wasn’t without Hope.

In the midst of the stem rust devastation, McFadden’s test rows of emmer/Marquis escaped the plague totally. “By the next year, the new variety was reliable enough to receive a name — Hope,†the 1999 Farm and Home Research journal reports.

Final stages of testing

It would be another three years — 1927 — before McFadden had sufficient quantities of seed to commercialize Hope.

While McFadden’s resume showed him as a college-educated farmer without a position in plant research, the obsessed scientist “knew who the world’s top wheat breeders were,†Kephart says. McFadden mailed them packets of 25 seeds to sow.

In the meantime, McFadden operated McFadden Seed Farm, selling conventional seed, and tilling Day County soil. Eventually, McFadden produced three successful lines with H49 officially becoming Hope, though it was susceptible to frost and black chaff.

But because of its rust resistance, when Hope was released in 1927 “seed firms actually offered a dollar for every rust spot any farmer could find,†Vietmeyer wrote.

Given the poor qualities that Hope inherited from emmer, the variety wasn’t destined to be the seed of choice.

The seed that saved the world

Vietmeyer wrote, “Despite poor (crop) performance, it proved a powerful parent. Blessed with wheat’s normal 42-chromosome set, it could endow other varieties additional anti-fungal protection.

“The genes McFadden had combined in a single seed in the borrowed backyard of a South Dakota boarding house eventually spread to millions of farms worldwide. In time this improbable gene set provided humanity’s top crop a uniquely powerful body armor.â€

During the war years of 1939-45, it is estimated that 15 million acres of Hope derivatives were planted. In 1943, U.S. wheat production totaled 23 million tons, up 3 million tons from 1939. The yields fed not only America and its troops, but millions of others worldwide.

In 1945, McFadden’s specimens were introduced to Mexico, where research was underway to make it and other developing nations become grain sufficient.

The result was the green revolution. A country changed not by the bullets of Pancho Villa, but by the germplasm extracted by an inquisitive and persistent farmer.

Kephart observes, “The Green Revolution started here in a backyard in Brookings, South Dakota, in 1916.â€

Dave Graves

Excellent overview of McFadden.

Thanks,

Ray G. Huey

Grandson of Edgar S. McFadden, Father of the Green Revolution.