I received a high-school diploma and prepared for college 50 years ago this June.

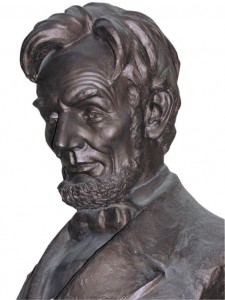

Although I was college bound – and had been since at least the start of my junior-high school years – I never once thanked either President Abraham Lincoln or Vermont Rep. Justin Smith Morrill. I never gave either of them a thought on commencement evening nor throughout the summer that followed or onto campus the next fall.

It never crossed my mind that my high-school commencement came exactly 100 years after the signing of the Morrill Act.

I should have thought about that a lot. I probably should have taken a moment to thank both President Lincoln and Congressman Morrill, too. Each of them helped make it possible for the land-grant college system to develop and for places like South Dakota State University to exist.

Without SDSU, I wouldn’t hold an undergraduate degree in printing and rural journalism. Without the Morrill Act, championed by the Vermont lawmaker and signed into law by Lincoln on July 2, 1862, there might not have been an SDSU when I was ready to go to a place from which I could go anywhere.

(Yes, I know. I just pretty much mangled one of South Dakota State’s better marketing slogans. If that bothers you, one question: Would you have written “when I was ready to go to a place I could go anywhere from’’ if both your kid sister and your beloved daughter were former or current members of the English faculty at South Dakota State? I didn’t think so. Neither would I.)

The Classics: Does H.S. journalism count?

The Morrill Act (and there was a pretty good piece about it in the last issue of State) was instrumental in making higher education accessible and affordable to the common citizen.

Prior to the passage of the act, higher education had pretty much been for the elite.

It focused on Latin, Greek, you know, the Classics. Those aren’t bad things, for sure.

I came close to taking Latin.

Actually, I took a course at Chamberlain High School from Merle Adams, the school’s Latin teacher. She also taught a journalism course and was advisor to the school newspaper. Journalism is the course I took, but my instructor could speak Latin. That’s close enough for me to say I almost took the language course itself.

I can say without question that having Mrs. Adams for a teacher was as close to the classics as I got until I started taking Mary Margaret Brown’s literature classes at State in the middle 1960s.

Land sales finance schools

Anyway, as I understand it, the Morrill Act was sort of the federal equivalent of South Dakota’s School and Public Lands program. South Dakota’s program identified school lands that were set aside for future development of public schools. A fund exists today that started with that program.

The Morrill Act allowed each state 30,000 acres of public land for each member it had in Congress. The endowment from the sale of the land, according to last month’s article, “would finance a college that emphasized agriculture, the mechanic arts and military tactics, without excluding literary or scientific studies.â€

My big brother was the first member of our family to go to college. My dad probably would have been a good college student. He loved to read, and he loved to argue ideas. He was from a generation, though, that didn’t routinely think of college as the next step after high school. My mom was from that generation, too, and while a few people from Lyman County were finishing high school and going off to college, it was pretty rare.

When I was a young boy, the very idea of going all the way from Reliance to Brookings for school was about like a journey to the center of the Earth or a trip to the moon.

My big brother was from the generation that was beginning to think of college as the next logical next step, and it was pretty important that a land-grant college existed for him. He earned a degree in animal science, and he made a South Dakota career in livestock buying, selling, sorting and feeding.

I showed up for the journalism program, and I did a stretch in the military program. I made sure I didn’t exclude the literary, and I even dabbled a little — with varying degrees of success — in scientific studies. (If only biology lab hadn’t been from 3-5 p.m. on Fridays, what a wonderful grade I might have earned.)

Legislation fulfilled its promise

Armed with my printing and rural journalism degree, I went everywhere from SDSU. I did nearly all of my traveling from a South Dakota base, mostly Pierre, but I met and interviewed people from all over the country in a 40-year newspaper career that was often exciting and nearly always rewarding.

My little sister followed, and so did my little brother. A generation later, two of my kids received degrees from State.

All of the Woster clan showed up on campus about a century after the signing, but you might say my family was what the folks who pushed the Morrill Act had in mind. Farm and small-town people, pretty common, hard-working, perhaps of limited means but not without means, and interested in gaining an education that would allow us to live, work and raise our families in different parts of our home state.

A person can’t ask for much more than that from one act of Congress.

By Terry Woster ’66