International scientists drawn to biotechnology lab, expertise

Top-notch laboratories, molecular biologists, pathologists and wheat breeders, along with a land-grant institution’s close relationship to its producers, have drawn visiting scientists from three countries to SDSU.

During the last six months, scientists from Algeria, South Korea and India have been learning how to develop wheat that can tolerate or resist disease and environmental stressors by genetically screening plant materials.

SDSU’s expertise in pathogens and genetics brought visiting scientist Hamida Benslimane from M’hamed Bougara University in Algeria here to learn about tan spot, using fungal specimens of Algerian wheat plants. She is working with assistant professor of biology and microbiology, Jai Rohila, and small grains pathologist Shaukat Ali.

Hamida Benslimane from M’hamed Bougara University in Algeria studied the pathogens that cause the wheat fungus tan spot; Dea Wook Kim from the National Institute of Crop Science in South Korea, analyzed preharvest sprouting; and Shahid Ahmed from the Indian Grasslands and Fodder Research Institute has tackled leaf rust.

Fighting tan spot in Algerian wheat

Benslimane spent 10 weeks at SDSU examining the pathogen itself and the genes and proteins that could lead to resistance to tan spot in wheat.

“This pathogen causes too much damage,†said Benslimane, citing up to 50 percent yield losses in North African wheat fields.

“Here I found people who have been working on tan spot for 20 years,†she explained. She worked with small grains pathologist Shaukat Ali to understand the disease. Then molecular biologist Jai Rohila of the biology and microbiology department helped her decipher what genetically makes one variety resistant and another susceptible to the fungus.

“I must first understand the pathogen before I can make resistant genotypes of wheat,†explained Benslimane, who brought fungal specimens recovered from tan spot-infected Algerian wheat plants to analyze their race structure. A different gene controls the resistance in each race of the pathogen.

“It’s essential to breed any cultivar to incorporate resistance to diseases,†explained Ali. Diseases can be managed with chemicals, but that method is expensive and can be tough on the environment.

“Having resistance in the variety is much better,†Ali said.

Benslimane learned the techniques that the SDSU experts use to unlock the secrets to resistance while also sharing her experience with Algerian tan spot.

Exploring preharvest sprouting

Only 1 percent of the 182 million bushels of wheat used in South Korea is locally grown, according to Kim. In 2008, the government set out to increase local production to 10 percent by 2017.

Visiting scientist Shahid Ahmed from India weighs agarose to prepare the electrophoresis gel, which he will load into the polymers chain reactor, or PCR, which uses electric current to separate the DNA into distinct bands, as part of his molecular work on leaf rust.

“We are trying to expand the area of cultivation and improve the quality and yield,†said Kim.

As part of a two-year project, Kim spent three months at SDSU studying why one line of wheat is more susceptible to preharvest sprouting than another.

Korean farmers raise white winter wheat, planting in October and harvesting in June; however, the country’s rainy season begins in June, explained Kim. If the rains hit the crop before it has been harvested, the grain begins to sprout in the head.

“It’s a problem everywhere,†said Rohila. “Just before harvesting, farmers don’t need the rain. When farmers can’t get in the field, ear loss and quality loss can happen.â€

White winter wheat is particularly susceptible to preharvest sprouting, explains Kim.

To help Kim improve preharvest sprouting tolerance in Korean wheat, SDSU wheat breeder Karl Glover provided Kim with 40 lines of wheat—half of them are tolerant to pre-harvest sprouting and half are susceptible.

“I did not expect this,†says Kim. He compared the lines to determine which functional proteins account for this tolerance.

Breeding resistance to leaf rust

Wheat is a major crop in India, with farmers raising nearly 95 million tons each year, according to Ahmed, a senior scientist and oats breeder at the Indian Grasslands and Fodder Research Institute. His work is supported by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research.

Leaf rust is an airborne disease, Ahmed explained. “If the wind blows, it carries the spores,†infecting both wheat and oats.

When conditions are conducive for leaf rust, it can affect 35 to 45 percent of the crop, reducing yields by as much as 45 percent, Ahmed explained. “It affects the quality of fodder oats.â€

Though farmers use chemicals to control the disease, Ahmed seeks to breed resistant varieties.

Now he must grow the whole plant population under disease conditions to determine if it is resistant to leaf rust, but at SDSU, he will learn how to “screen that breeding material at an early stage rather than going to the full-scale field.â€Â It’s called marker-assisted selection.

To do this, Ahmed worked with molecular biologist Yang Yen, who is experienced in molecular marker-assisted selection. He used the resources at the plant biotechnology lab to accomplish this, thanks to his host, Rohila.

By screening the DNA of several wheat breeding lines using modern biotechnology tools, Ahmed can extract the genetic material from a plant leaf, compare it with a resistant or susceptible parent from the cross and then can tell whether the offspring will show a resistant or susceptible phenotype to the disease.

“We can test the breeding material at a molecular level,†he said. Being able to promote or reject a line without growing the plant in the field will speed up the process of breeding for resistance in Indian grain.

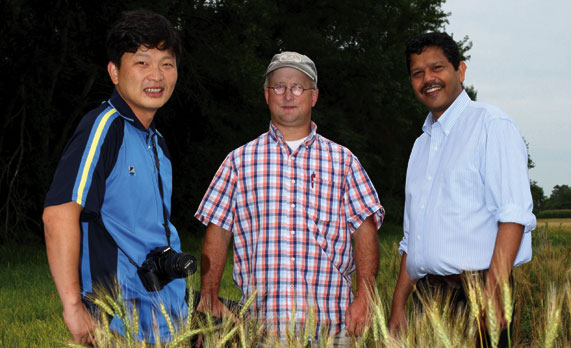

Visiting scientist Dea Wook Kim, left, from the National Institute of Crop Science in Suwon, South Korea, examines South Dakota wheat to unravel the genetics behind resistance to preharvest sprouting. Spring wheat breeder Karl Glover, center, supplies the wheat varieties and molecular biologist Jai Rohila provides the genetic expertise.

As was done for Kim, Glover provided Ahmed with lines that are resistant and susceptible to leaf rust. Ahmed arrived in Brookings on Nov. 2 for a three-month stay.

“I’m getting trained in these good techniques that can be utilized in a breeding program, that will help us speed up the varietal development process in fodder oats,†Ahmed explained.

In selecting a research setting, Ahmed said, “I looked for a place working on biotic and abiotic stress with good molecular techniques.†The combination of the excellent laboratory facilities, team of specialists and proximity to farms and fields led him to SDSU.

“It’s a large village with all the best facilities,†he said. “This lab can compete with any in the world.â€

Christie Delfanian