Public higher education changed forever July 2, 1862.

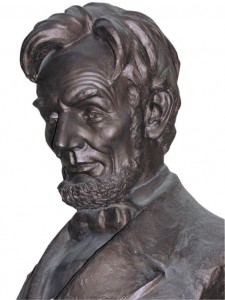

That’s the day President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Act into law, creating the framework for a system of land-grant universities that is still thriving today.

The country’s keen interest in furthering higher education can be seen in the circumstances surrounding the signing of the Morrill Act. The nation was embroiled in a civil war. The week Lincoln signed the Morrill Act, the Union and the Confederacy fought three of the bloodiest battles of the war. With all that going on, Congress and the president still had the foresight to change public higher education forever.

However, as with most things that come out of Washington, D.C., there was politics afoot.

Representative Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont first shepherded his legislation through Congress in 1859, only to see it vetoed by President James Buchanan.

The circumstances were different in 1862. Southern states had left the Union, and they were the most serious opponents of the Morrill Act. Southerners clung to the classical model of education that was meant for the well-to-do and aristocratic. They also had a healthy suspicion of any act that allowed the federal government a role in education.

The passage of the Morrill Act was the culmination of years of distrust and disillusionment with an education system meant for the elite, teaching a curriculum of Latin and Greek languages, and classic European literature.

The system’s detractors sought a more democratic system of education, open to everyone and teaching subjects that would help farmers produce more and train the skills needed to build a nation.

With the southern states out of the Union and out of the way, the Morrill Act breezed through Congress by hefty majorities in both houses.

Morrill’s legislation allowed each state 30,000 acres of public land for each member it had in Congress. The endowment from the sale of the land would finance a college that emphasized agriculture, the mechanic arts, and military tactics without excluding literary or scientific studies.

Eastern seaboard states had little or no public land so they were allowed their land-grants in the nation’s western holdings where savvy leaders chose land with fertile soil or heavily timbered forests.

The size of the grant sparked opposition from some western interests who feared all their land would be lost. In total, the Morrill Act of 1862 granted states just more than 17.4 million acres, an area larger than the size of present-day West Virginia.

These land-grants would foster a sea change in education, making it as egalitarian as it was practical. Its implementation would provide the leaders and workers needed to rebuild a nation torn apart by the Civil War and then help that reunited nation achieve its Manifest Destiny.

Celebrations will mark anniversaries of Morrill Act, Hatch Act

Barry Dunn doesn’t mince words when he’s talking about the Morrill Act: “All public higher education owes itself to the Morrill Act.â€

The act, which became law in 1862, granted land to all states. The sale of that land would be used for the creation of public universities.

“Its impact on opening the doors for the common man to obtain an education is one of the pinnacles of history,†says Dunn, dean of the College of Agriculture and Biological Sciences.

South Dakotans were eager for the kind of education delineated in the Morrill Act. So eager, that they got started on their land-grant seven years prior to statehood.

“South Dakota State is older than the state itself,†Dunn says.

In 1881, Brookings lawyer James Scobey set out for the territorial Legislature in Yankton with two goals: secure a plum government appointment for his law partner and see to it that Brookings would be the home of the penitentiary.

He failed on both counts.

In what might be seen as accepting a consolation prize, Scobey secured for Brookings the rights for a college in the southern half of Dakota Territory.

The value of the Morrill Act was enhanced on March 2, 1887, by the passage of the Hatch Act that established agricultural experiment stations in connection with land-grant institutions to conduct research and produce the findings for the public.

“It opened the doors for the scientific methods of discovery to be applied to agriculture,†Dunn says.

That method allows scientists to test a hypothesis and publish their results. According to Dunn, prior to the Hatch Act, all farmers could rely on was their powers of observation. “All they could do is say, ‘That plant is taller than that plant.’â€

SDSU is planning in 2012 to mark the 150th anniversary of the Morrill Act and the 125th anniversary of the Hatch Act.

The events, still in the planning stages, will help raise the profile of two important acts that set the course of public higher education in the nation and in South Dakota.

“The scientific breakthroughs in this land-grant and every other land-grant are the cornerstone of agriculture,†Dunn says.

Dana Hess