Grad seeks to protect power grid from solar flares

When the topic is natural disasters, John Kappenman thinks big.

When the topic is natural disasters, John Kappenman thinks big.

He’s not concerned about tornadoes or flooding. He’s not worried much about earthquakes or avalanches. He doesn’t even get worked up about a tsunami.

His concern is of a larger magnitude—the kind of natural disaster that would make Hurricane Katrina look like a waterspout. The kind of disaster that would decimate life as we know it. The kind of inevitable disaster made all the more horrific by the fact that its effects are preventable with the right precautions.

Since shortly after he graduated from State in 1976 with a degree in electrical engineering, Kappenman has been studying the effects of severe solar flares, in particular the danger those flares pose to the nation’s power grid.

“We built a high-tech infrastructure without any awareness of how catastrophic these threats could be,†says Kappenman. “It’s something that could put millions of lives at risk.â€

His first and longest assignment

Kappenman has been studying solar flares and the threat they pose to the power grid since he started his engineering career with Minnesota Power.

“It was one of the first assignments I got when I graduated from South Dakota State University,†Kappenman recalls. “We thought it was a small problem that could easily be solved. That’s why I got stuck with it.â€

It came from outer space

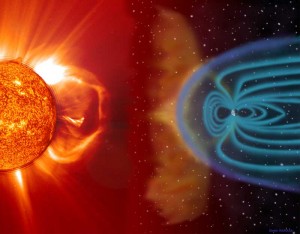

A solar flare packing enough power would be capable of generating a blast of energy so strong that it could knock out the electrical grids over most of the planet, putting millions of lives in jeopardy.

While it may sound like the plot of a bad disaster movie, it’s not science fiction. It’s science fact.

According to Kappenman, it’s not a matter of if the solar flare will take place so much as it’s a matter of when.

“The odds are 100 percent,†Kappenman says of the likelihood of such a large blast of energy from the sun. “There’s nothing more certain.â€

Solar storm blasts Quebec

Kappenman and others concerned about the threat from solar flares point to March 13, 1989, when two solar blasts knocked out power in Quebec. For nine hours millions of customers were without electricity. While that’s hardly a disaster, it may be a harbinger.

Kappenman notes that the 1989 solar blasts were one tenth of the size of flares that struck Earth in 1859 and 1921. Fortunately, in 1859, much of society was not electrified and even in 1921, the power grid was not developed to the point where it played a significant role.

A solar storm of the magnitude that reached Earth in 1859 or 1921 would melt or burn out the copper windings and leads in high voltage transformers, ushering in a modern version of the Dark Ages.

“Through the work that we’ve done, we know it’s probably one of the largest natural disasters that could happen,†Kappenman says.

That work has led Kappenman to form his own company, Storm Analysis Consultants. From his base in Duluth, Minnesota, Kappenman has taken his message to lawmakers, policymakers, and power company executives.

Kappenman’s travels have taken him from the committee rooms of Congress, where he has testified about the power grid’s vulnerability, to power company boardrooms, where the leaders of utility businesses are looking for answers.

In 2010 Kappenman was among a panel of experts featured in Electronic Armageddon, a program about the threat of solar flares that aired on the National Geographic Channel. In the course of a few weeks in the fall, Kappenman was a presenter at the First World Summit on Infrastructure Security in London, England; he took his message to the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania; and he worked as a consultant in New Mexico.

Progress as more hear the message

After years of describing a threat that sounds too incredible to be true, Kappenman finds that people are beginning to listen to his message.

Legislation in Congress would mandate coordinated action against the threat posed by solar flares. That threat, according to Kappenman, starts with the flare and impacts Earth through a geomagnetic storm caused by the flare. The geomagnetic storm then disrupts the power grid.

Kappenman, of course, is an engineer. Show him a problem and he’ll look for a way to fix it. And a fix does exist to protect the power grid from solar flares. It just won’t be easy.

Kappenman likens protecting the power grid to making a building earthquake safe after it has already been built.

“Realistically, the best response is to modify the design of the current power grids,†Kappenman says, noting that weather-related protections have been worked into the grid in the past. Protecting against solar flares could be accomplished by adding protective devices—think of them as larger, much more expensive surge protectors—to the grid.

“It’s not that expensive in the grand scheme of things,†Kappenman says of the upgrade.

100 companies need to take action

Even if Congress mandates protecting the grid, coordinating the effort would be a Herculean task.

“In the United States, there are about 100 large companies and organizations that would have to act in a coordinated fashion,†Kappenman says.

In the meantime, Kappenman soldiers on, taking his message to anyone who will listen. And, despite a growing consensus that something needs to be done, the power grid remains unprotected against a disaster that’s heading for Earth just as surely as the sun coming up in the morning.

By Kappenman’s calculations, the frequency of solar storms is erratic, occurring between once every thirty years and once every 100 years.

“They will occur again,†Kappenman says. “Given sufficient time, it is a certainty.â€

Dana Hess