Retired SDSU administrator recalls triumph, strife of Briggs, Berg eras

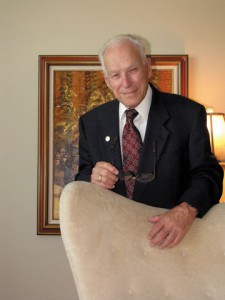

With a light chuckle and a gleam in his eye, Harold Bailey recalls the story that turned the pharmacist turned administrator into a historian.

At a 125th anniversary banquet for South Dakota State University in 2006, V.J. Smith, then the executive director of the SDSU Alumni Association, caught up with Bailey, a vice president emeritus for Academic Affairs.

An animated speaker, V.J. Smith pointed his finger in Bailey’s face and said, “‘Harold, you have no right to keep those secrets to yourself,’†Bailey recalls.

The secrets weren’t scandals but rather the inner workings of South Dakota State University from 1951 to 1985, the thirty-four years that Bailey worked at SDSU. Smith was particularly interested in Bailey’s perspective during the years he worked in campus administration.

The pharmacy department head served as chief academic officer at State from 1961 to his retirement in 1985.

In the decade from 1960 to 1970, the “cow college in Brookings†went from 3,050 students to 6,257.

State faced constant challenges

During the presidency of Hilton M. Briggs (1958-75), State went from being a college to a university, experienced an unparalleled building boom, stepped into the first technology explosion, and largely sidestepped counterculture explosions blasting campuses nationwide.

Enrollment growth slowed considerably during the years of President Sherwood Berg (1975-84), but “during the Berg era the University was constantly besieged by money issues,†Smith says. “I don’t think our state leaders had the same vision for the University as Bailey, Briggs, and Berg.â€

As a result, Bailey calls 1975 to 1985 “the decade of unrest.†There were efforts by the Legislature to create a single university system, a $500,000 budget cut brought on by a struggling ag economy, and a move by the Regents to eliminate degrees and reallocate funds.

Those challenges had been preceded by the Regents’ attempt to remove the engineering college from State during the Briggs administration. Aided by Briggs likening that move to a rancher castrating his prize bull and the Bibby Bill, legislation by state Senator John Bibby blocking the plan, the Regents’ effort died.

“It’s all in the book,†Bailey says in a July interview.

Ready to go to press

The book—A Quest for Excellence or On Creating a Major University from a Small State College—is a memoir of Bailey’s time on campus, particularly from 1958 to 1984. It was five years in the writing, and there’s minor editing left to be done, he says on its 545 pages, including index and tables. After that, copies will be available at local bookstores this fall.

Smith says “I’m glad it’s come to this point, and not just for Harold but for the sake of the University. It’s so much a part of what we are today. He saw a lot. He did a lot.â€

The nice guy prevailed

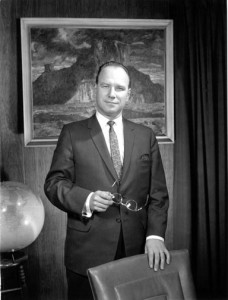

Harold Bailey stands for a formal portrait in the President’s Office in the early 1970s. In a book being published later this year, Bailey gives a detailed look at the history of SDSU during his tenure at State from 1951 to 1985 with a particular emphasis on the years he served as chief academic officer (1961-85).

That thought is echoed by Berg, who noted that as chief academic officer Bailey was an advocate of teaching effectiveness and a friend of faculty.

Not to mention being a nice guy.

Smith says, “He [Bailey] is such an intelligent, caring human being. He always had the good of another person in front of him. I never heard him speak disparagingly of another person.â€

During the interview at his south Brookings home, Bailey didn’t use the occasion to speak ill of Ray Hoops, who early into his seven-month term as SDSU president demanded Bailey’s resignation. That came first thing on a Monday morning a couple months after Hoops began his job July 1, 1984.

“I couldn’t understand why he wanted to do that,†Bailey recalls of the order to turn in his resignation by 5 p.m.

He recalls telling Hoops that there might be some negative reaction from the faculty if the first major action of the new president is to fire Bailey, who continued with his work schedule that day. After a meeting with Hoops and the engineering dean, the president asked Bailey to stay afterwards.

Hoops said Bailey could stay for a year, but he wanted his resignation. Hoops said he needed someone in the position who could “wake up a slumbering elephant,†Bailey recalled.

Bailey complied with Hoops’ request, but it was Hoops who awoke discord with other academics on campus and the Board of Regents, which lead to his dismissal in March 1985.

Bailey did retire June 30, 1985, at age 63, but it was Hoops who left town in controversy and in a lawsuit fight with the Board of Regents. (He was, however, able to rebound in his academic career and spent fifteen years as the president of Southern Indiana.)

When Bailey retired, the Board of Regents honored him with the rank of vice president of academic affairs, emeritus and distinguished professor of higher education. In addition, Governor William Janklow designated June 30, 1985, as Harold S. Bailey Jr. Day in South Dakota.

Still receiving honors 26 years later

In 1994, the University honored Berg and Bailey by naming new upper classmen residence halls in their names.

This fall, Berg Hall became Meadows South while Bailey Hall became Meadows North as Residential Life markets the previously upperclassmen dorms to sophomores. Berg, whose career before becoming president was in agricultural economics, had his name attached to Ag Hall in May.

At a ceremony November 3, Bailey’s name will be attached to the Rotunda classrooms.

Bailey says SDSU officials told him that his “name fits more perfectly with an academic building, and I agree with it. I’m very comfortable with it.â€

This year’s distinguished non-alumnus

The dedication is part of a big week for Bailey. November 4 he will be honored by the SDSU Alumni Association as a distinguished non-alumnus and the next day he will ride in the Hobo Day parade with the 2011 class of distinguished alums.

Bailey’s children—Cynthia, Lynda, Gwen, Pamela, and Harold III—will be in town for the events. Bailey, who was married to Barbara Ann Dewey from 1946 to 2008, has twelve grandchildren and fourteen great-grandchildren, including Harold Bailey IV.

“I claim my life has been a blessing to me,†says Harold Bailey Jr., a Springfield, Massachusetts, native.

This is the second time for Bailey to be named a distinguished alum. Purdue University School of Health Sciences, which awarded him his doctorate in pharmaceutical chemistry in 1951, named Bailey a distinguished alum in 1998.

In addition to other academic honors, Bailey received the Brookings Bar Association’s Liberty Bell Award for community service in 1997.

Like George Bailey, it’s been ‘a wonderful life’

Reflecting on the list, Bailey says, “I think this [SDSU non-alumnus award] is one of my top honors; to be recognized by the alumni. I was really surprised. I’ve had a wonderful life, including the sixty-two years married to a most wonderful woman, Barbara. She was a great source of strength and support during my career.â€

On top of that, Bailey, 89, has been blessed with good health and a sharp memory of SDSU history.

In writing Quest for Excellence, Bailey says, “I very liberally used the Collegian [the SDSU student newspaper] as a backup of what I remember. I go back to the Regents’ minutes and the Collegian to make sure it’s all accurate.†In some cases, he consulted past colleagues or their family.

V.J. Smith remembers telling Bailey, as he began his writing in 2006, “Don’t cheat us from knowing what really happened.â€

Bailey says his memoir is on target. “I think it’s about as accurate as any of them could be.â€