Scholarship keeps Briggs connected to campus

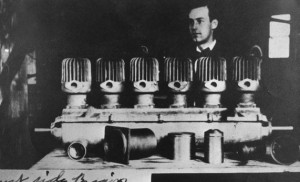

In 1906, in an engineering lab at South Dakota State College, a student named Stephen F. Briggs created a small, experimental engine. Legend has it that the engine was remarkable, if only for the amount of noise that it made.

Briggs’ career flourished after college as he continued to make a considerable amount of noise in the world of commerce, using a sharp head for business and his innate curiosity to produce everything from car locks and ignition switches to small engines that powered refrigerators, lawn mowers and watercraft.

It was a college connection that got Briggs started on his career. His SDSC basketball coach, Bill Juneau, knew Briggs wanted to go into business and introduced him to his former neighbor, successful Wisconsin grain merchant Harold Stratton. This was the start of the partnership that would create Briggs & Stratton, a company that’s still successful today, but, like many new ventures, had its start in failure.

The first undertaking of the new company was the construction of six-cylinder, two-cycle engines but they proved to be too costly to manufacture. Next they sought to take advantage of the booming automotive industry by assembling cars from parts that were manufactured elsewhere. This proved to be unprofitable.

From locks to loaded grenades

Targeting a niche market in the automotive industry, the business found success creating locks, ignition switches and specialty parts.

From the start, Briggs & Stratton reflected Briggs’ keen curiosity for new ideas and new ventures. With a firm grip on the automotive specialties market, the company branched out into small engines, refrigerators and radios. In World War I, the Briggs Loading Company was formed to assemble, load and pack 1 million rifle grenades.

In 1929, Briggs helped organize the Outboard Motor Corp., which went on to produce Evinrude engines for watercraft. Briggs resigned as president of Briggs & Stratton in 1935, continuing to serve as chairman of the board. Succeeding him as president was his former SDSC basketball teammate, Charles Coughlin. In 1936, Outboard Motor Corp. merged with Johnson Motor Co. to form Outboard Marine Corp. with Briggs serving as its president.

Focus went beyond boats

Briggs retired from the board of Briggs & Stratton in 1948 to work full time at Outboard Marine Corp.

“Briggs, whose engineering brilliance and business acumen had created an industrial giant, gracefully left the company he had created,†Jeffery R. Rodengen wrote in his history of the company, “The Legend of Briggs & Stratton.â€

A company history book is likely to put the best spin on any development, but Rodengen is refreshingly honest in his acknowledgement that with the departure of Briggs, the company lost its propensity for experimenting with new businesses, concentrating on small engines and automotive locks and accessories.

Briggs was chairman of the board of Outboard Marine until 1963 and he served as a consultant for the company for years after that. By 1963, Outboard Marine’s roster of goods reflected Briggs’ curiosity for new products and his willingness to take on new challenges, producing a wide variety of boats and motors as well as power mowers, golf carts, utility vehicles, snowmobiles and chain saws.

Scholarship strengthens campus connections

His college basketball coach introduced Stephen F. Briggs to the man who would be his longtime partner. His former college basketball teammate was an important executive in the company he started.

The connections Briggs made in college followed him throughout his life and he never forgot that. Briggs renewed that college connection when, as an accomplished industrialist, he turned his attention to his alma mater in 1958 to start a scholarship.

Originally funded by regular checks from Briggs, the scholarship was endowed with a $2.8 million gift from Briggs in 1993. Subsequent gifts included $1.1 million from the estate of Briggs’ wife, Beatrice, and $950,000 from the Eleanor Sweet Charitable Trust.

The program is evaluated each year with a certain number of students being named Briggs Scholars. Half of the students selected are engineering majors while the others come from across the university.

In his book, “South Dakota State University: A Pictorial History 1881-2006,†former history professor John Miller refers to the Briggs Scholarship as the “gold standard†for scholarships at State.

Burns recalls impact of scholarship

“It is still one of the most cherished of scholarships that’s offered at South Dakota State University,†says Bob Burns, distinguished professor emeritus of political science and dean emeritus of the Honors College. “It was a great honor to be a Briggs Scholar, and it still is.â€

Burns should know; he was in the second class of Briggs Scholar recipients in 1960. At the time, Burns recalls, the $500 scholarship paid roughly half of his college expenses.

“Without the scholarship, I would have struggled greatly financially,†Burns says.

Now the Briggs Scholarship offers a renewable four-year scholarship worth $6,500 per year, still roughly half the cost of a year’s education. For the 2012-13 academic year, eight new students will receive Briggs Scholarships bringing to 35 the number of Briggs Scholars on campus.

During his junior year, Burns was privileged to meet Briggs during one of the industrialist’s rare visits to campus. The scholarship and the man made an impression on Burns who in turn formed his own strong connection with campus. Burns eventually worked his way back to campus as a professor, serving for years as the adviser to the Briggs Scholars group and taking part in the interviews of students who were seeking Briggs Scholarships.

“It all goes back to that letter from admissions,†Burns says of the letter announcing his selection for a Briggs Scholarship and starting his lifelong connection with SDSU. “Who knows how my life would have turned out differently otherwise?â€

Dana Hess