1933 suit sought to strangle definition of land grants

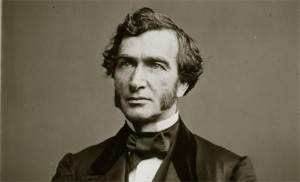

His long and frizzled mutton chop sideburns would have been the envy of any of our furry Weary Wils who over the years have proudly led the Hobo Day parade.

And Congressman Justin Smith Morrill also had an idea that at the time some thought rather long and fizzled. He stroked his coiffed chops in 1862 and paraded a visionary new plan on the floor of the House of Representatives.

Morrill had this “hairbrained†scheme of offering a quality educational experience to America’s masses who were unwelcome and financially unable of attending high society’s schools of the day, elite places patterned after European models that catered to the wealthy and the politically connected.

He envisioned a system of higher education for all classes. It would, of course, teach subjects to help farmers be more productive. But it would also provide common citizens with the various skills and mastery needed to collectively build a nation.

Latin and Greek languages and classic European literature taught to the upper class wasn’t going to cut it in post-Civil War America.

Thus the Vermont native’s famous Morrill Act spawned the land grants, including South Dakota State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts.

‘Kiddish trick’ threatened college

Our state’s land-grant college eventually sprouted, grew and prospered, only to face new challenges years later because of the often misunderstood land-grant concept. One test came in 1933.

The times and the budgets were stressful enough in South Dakota in those dreary, dusty 1930s, and State College had meet painful, state-mandated reductions, responding with the largest cut of any school in the system.

Now things got even more dicey with this cataclysmic kick in the mutton chops.

State College was targeted for massive program gutting by what one state newspaper editor described as a “kiddish trick†devised by a group of Vermillion businessmen and University of South Dakota alumni who were, the editor concluded, “green with envy.â€

Mines also named in ‘friendly’ lawsuit

That group brought a lawsuit (they called it “friendlyâ€) to the South Dakota Supreme Court that contended the state’s Board of Regents had exceeded the precepts of the 1862 Morrill Act.

The bombshell was lobbed in May 1933. Even the School of Mines was caught up in its trajectory. The Hardrockers would lose civil, electrical and mechanical engineering.

But the lawsuit’s most traumatizing section contained what the editor of the Sioux Falls Argus Leader said would be “a drastic blow†to State College. That was an understatement.

The petition claimed that more than 60 programs and courses at State College should not have been allowed by the Regents, including civil, mechanical, electrical and chemical engineering, journalism, all commercial and business programs, education, mathematics, physics, art, language, history, pharmacy, general science, political science, chemistry, psychology, and many others.

That wasn’t the end of it. The petition’s hit list included: “all graduate level courses not confined to agriculture or the natural science connected with agriculture or those sciences bearing directly upon the industrial arts and pursuits.â€

Unanimous verdict made today possible

The State College Alumni Association was stunned. President Elmer Sexauer ’09 asked members who had gone on to law school to offer their pro bono service. Hundreds of other graduates and friends stepped forward to help, and an angry student body of less than 700 mobilized.

State College alumni had dutifully refrained from protesting the recent understandable Board of Regents-ordered Depression-required reductions, but felt they now must speak out against this added legal effort to put what some called the “cow college†in its proper place in the state’s higher education’s pecking order.

As lawyers argued before the Supreme Court in June 1933, the Morrill Act was a consistent reference, its wording the most convincing of advocates.

On Sept. 7, 1933, the justices unanimously denied the University of South Dakota group’s application.

It had been a trying summer for the college on the hill.

The Brookings Register observed: “Veteran members of the college faculty, who have always had State’s welfare and growth at heart, have added years to their lives. State College can now continue its solid growth and forge ahead.â€

State College did just that, and although more similar challenges loomed in the future, South Dakota’s land-grant treasure is today the largest, most diverse and the most research active by far in the state.