Before Neil Armstrong took a “giant leap for mankind†on the surface of the moon, astronaut Ed White stepped out of the Gemini IV spacecraft and embarked on

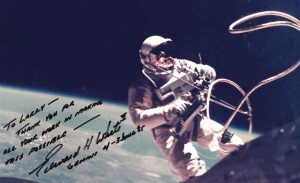

A signed picture of Ed White on the first American spacewalk. The photo was a gift from White to Bell.

America’s first spacewalk. A team led by Larry Bell ’58, designed the life support system that allowed this turning point in the space race. This June marked the 50th anniversary of Gemini IV’s flight.

Early years

Bell grew up on a farm in the Doland area where he enjoyed mathematics and working on machinery. He knew he wanted to be an engineer but always assumed he would someday go to the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology.

When Bell applied for scholarships, he received one for the Illinois School of Technology in the heart of Chicago. Upon arriving in the big city, it didn’t take long for the South Dakota farm boy to seek his education elsewhere. By the time Bell returned to South Dakota, the School of Mines had already begun classes, but SDSU had not. It was there Bell began his engineering journey.

“I have great memories from SDSU,†said Bell. “I liked my professors and always really enjoyed Hobo Day.â€

Bell and his friends even fixed up a Model-T that had been sitting in a field and drove it through the Hobo Day parade one year.

After four and one-half years studying mechanical engineering and thermodynamics, Bell graduated in December 1958. He was interested in a career in aircraft manufacturing, but found a position with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in Omaha working on ATLAS missile sites and the propellant loading systems.

Road to NASA

A few years later, several of Bell’s friends went to work in Cleveland at the Lewis Research Center. Bell also applied, but the Cleveland location was fully staffed.

His resume was sent to the Langley, Virginia, Research Center where he was offered a position with the manned space program.

“While I was thinking about it, my wife said she’d follow me anywhere except overseas or Texas,†said Bell.

The space program moved from Virginia to Houston shortly thereafter. His wife eventually gave in and agreed to give Texas a try, and on Jan. 2, 1962, Bell started work as the fourth engineer hired for the Manned Spacecraft Center, now the Johnson Space Center.

“When the program moved to Houston, we didn’t really have a building to move to,†said Bell. “They rented a pipe factory, office buildings, some offices above an appliance store, anywhere they could find some space to work.â€

The early days of NASA saw quick and substantial growth. Bell’s first projects were in environmental control and life support with the Mercury program, America’s first manned space missions. His responsibilities involved development of system improvements and early planning for a two-man Mercury, which later became the Gemini spacecraft. Other NASA employees were already engaged in advance planning and study phases of far-off projects such as a lunar base.

“It was a lot of being in the right place at the right time,†Bell said. “I didn’t get the Cleveland job that I’d originally wanted, but I got this other great opportunity. It was some good luck.â€

After a few years in Houston, NASA built permanent offices and began work on the Gemini missions. While the Mercury program aimed to orbit a one-man spacecraft around the earth, study his ability to function in space and safely return him to the surface, the two-man Gemini missions were designed to take space travel to the next level, including docking a spacecraft and studying long-term duration in space. The first American spacewalk—also known as extravehicular activity or EVA—was projected for Gemini VI.

The spacewalk challenge

Bell got the call the morning after he returned home from supporting the Gemini III mission at Kennedy Space Center. The Soviet space program had successfully completed an EVA one week earlier and NASA wanted to rise to the challenge—six months ahead of schedule.

Bell displays a model of the Buran, Russia’s version of the Space Shuttle. The Buran was a gift from a Russian project manager.

“I told them we’d have to take the simple approach, but I could start putting plans together,†said Bell, who led the task team responsible for the EVA hardware. He was 28 years old.

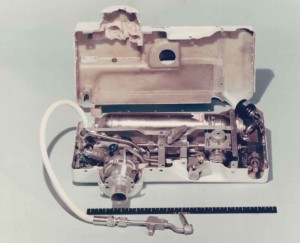

By repurposing parts that had already been created for the Gemini spacecraft, including oxygen pressure vessels taken from a previous ejection seat, Bell theorized his team could configure an open-loop system that would allow an astronaut to maintain body temperature and receive oxygen for a short EVA, if the astronaut did not exert himself too much.

The morning after the phone call, work was underway, though kept secret from the public and a majority of NASA personnel. Fewer than 50 people knew about the plans to fast-track an EVA.

“The astronauts were excited,†said Bell. “Ed White started showing up at night to watch our tests and he used the system in a vacuum chamber. We did almost everything at night after people had gone home for the day. It was kept very quiet. The drawings and hardware were all labeled as a chamber vent system as a cover-up. We didn’t want people to know we were working on it, just in case it didn’t work out.â€

The team’s compressed schedule took a toll. Bell recalls working days without going home, catching an hour of sleep at his desk when he could.

The moment of truth

The Gemini IV spacewalk was scheduled for June 3, 1965. Bell sat at the elbow of the man in charge of the mission so he could be available for any questions. Other members were stationed in Hawaii and Bermuda in case Houston’s mission control lost communication.

“I was a nervous wreck, yet I was still confident,†Bell said.

White, attached to the spacecraft by a 25-foot umbilical cord, was able to control his movements with a handheld maneuvering unit, also called a “zip gun,†which released pressurized oxygen.

After 20 minutes, mission control called for White to re-enter the spacecraft, mindful that he must not exert himself too much. Bell recalled White saying that moment was the saddest moment of his life.

After Gemini IV

For a number of years following the EVA, Bell had a photo in his office from Ed White that read “Thank you for all your work in making this possible.†One day, the photo was stolen. White promised to get him a new photo but died in a fire during prelaunch testing for the first manned Apollo mission. Bell’s original photo was later found in a desk at NASA and returned.

Bell worked with NASA until 1994, at which point he became a consultant with Boeing, working on a microgravity system for use on the International Space Station. He retired in 2010 after 47 years at Johnson Space Center.

He remains humble about the eight weeks of intense work that went into making the first American spacewalk a reality. “I was extremely fortunate to live during those times. Right place, right time.â€

Madelin Mack

Even though this is a story about myself, I must give credit to the staff at the STATE for doing a great job of taking a lot of information and making a very nice summary article.